Project & Brief

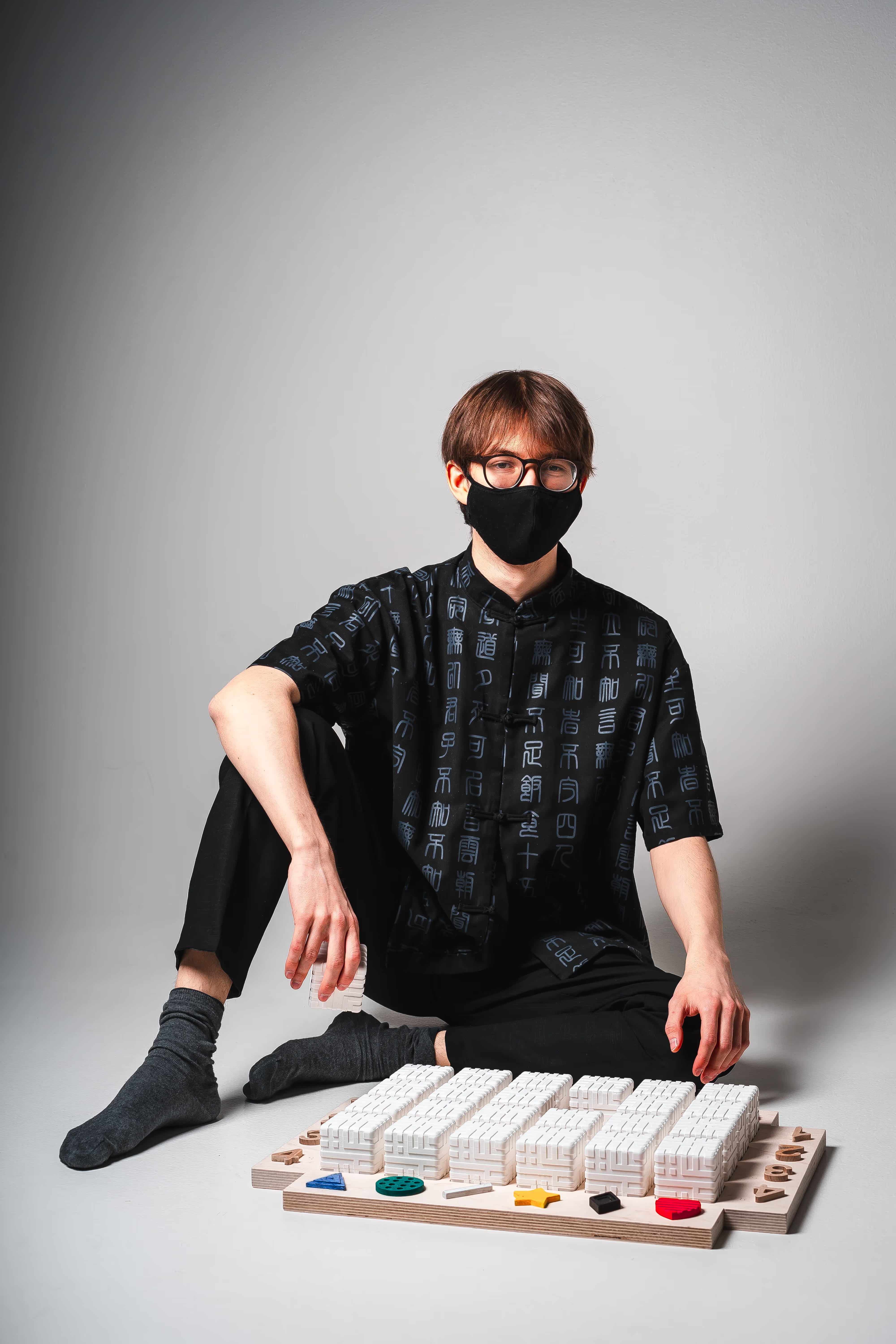

Play is a fundamental right, enshrined in Article 31 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and a powerful developmental tool. Yet for blind and visually impaired children, play is often inaccessible, isolating, or adult-guided.

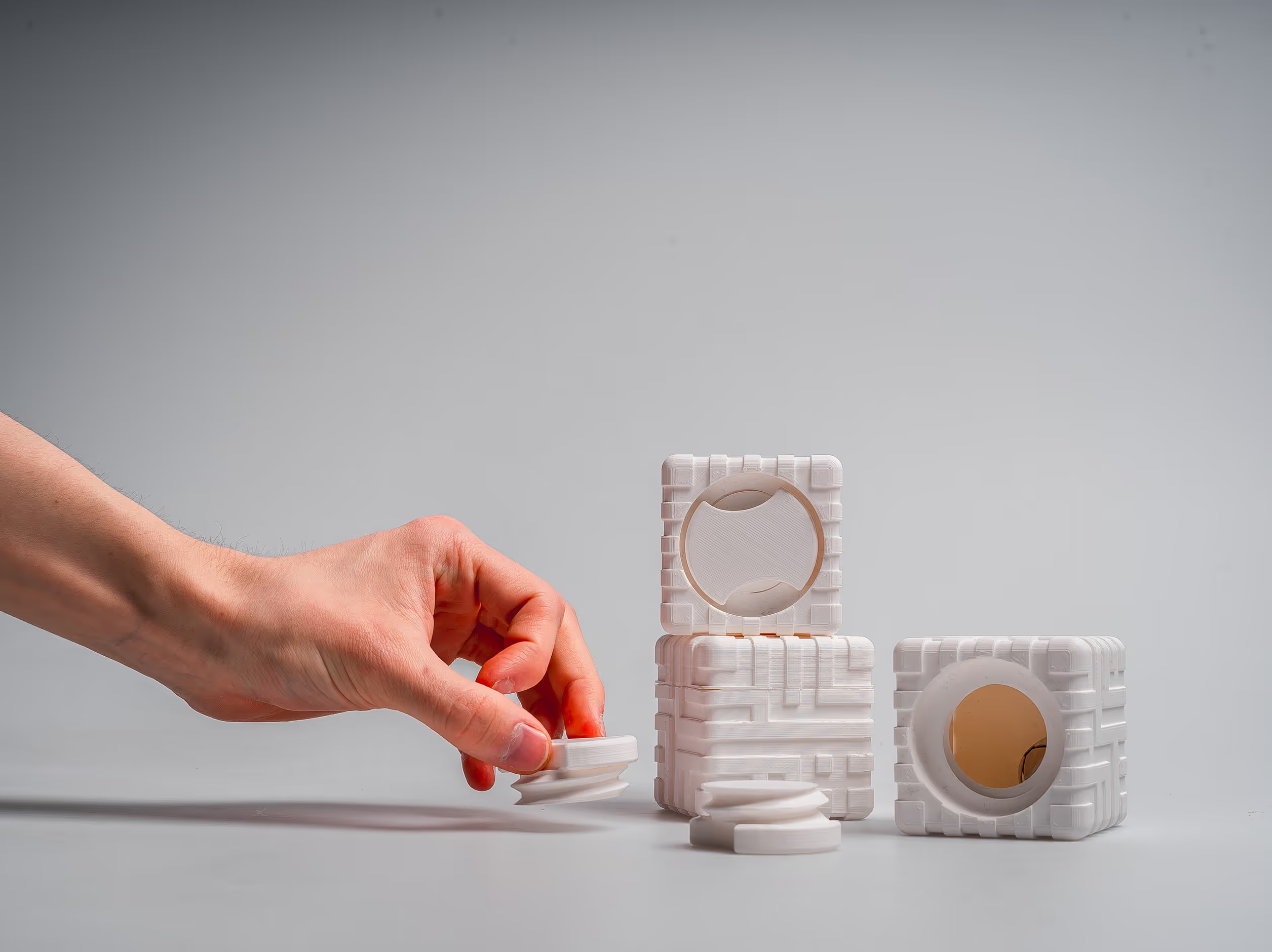

This was a foundational solo project in which I explored how design can create inclusive environments for children with visual impairments. The goal was to bridge the developmental and social gap in play between blind and sighted children by designing a game that encourages equal participation, shared strategies, and mutual joy.

The Core Challenge

"Design a shared experience to integrate visually impaired children into common classrooms."

Key aspects of the brief

Equality ⚖️

Ensure equal opportunity to strategize and win for both blind and sighted players

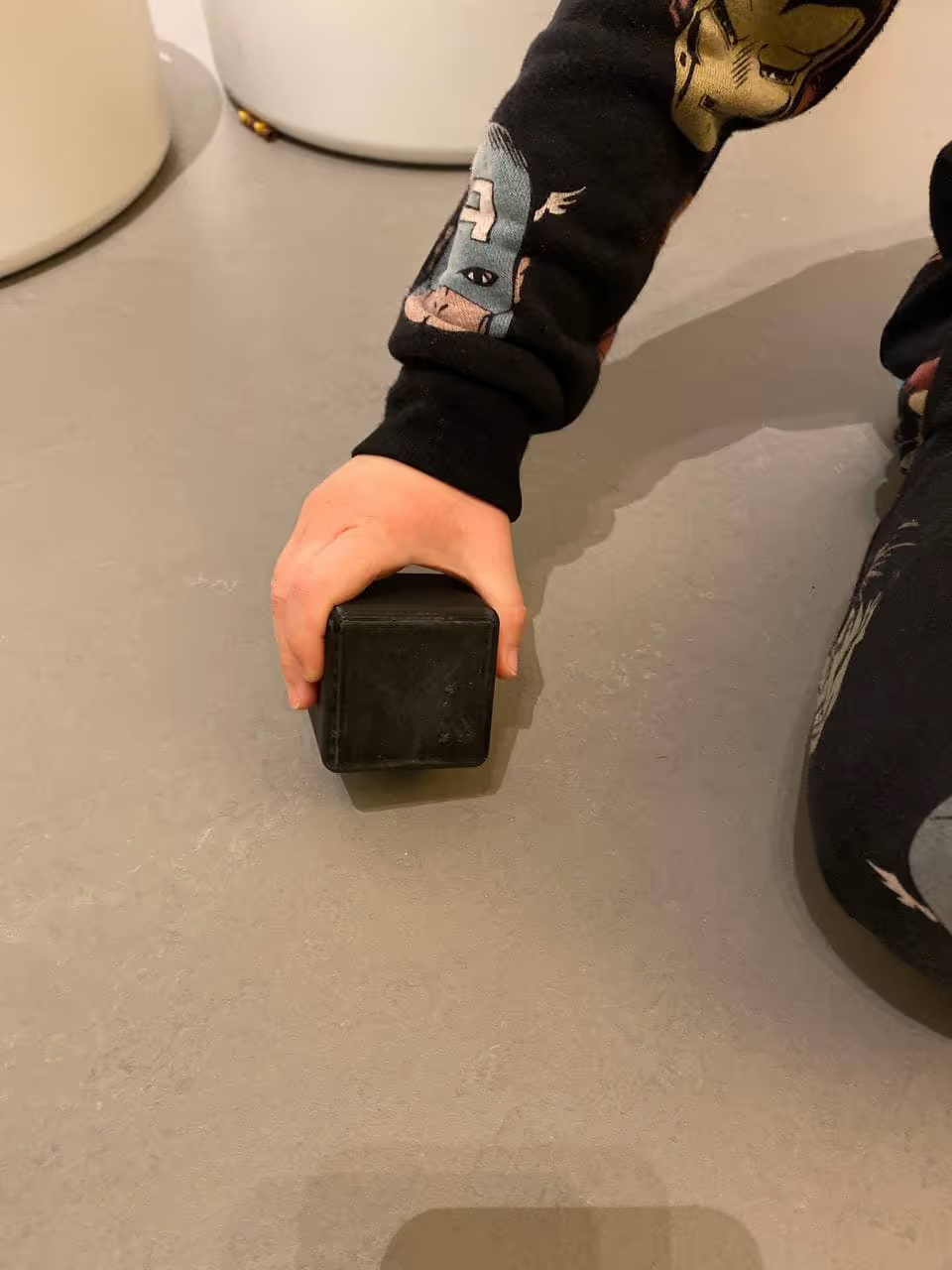

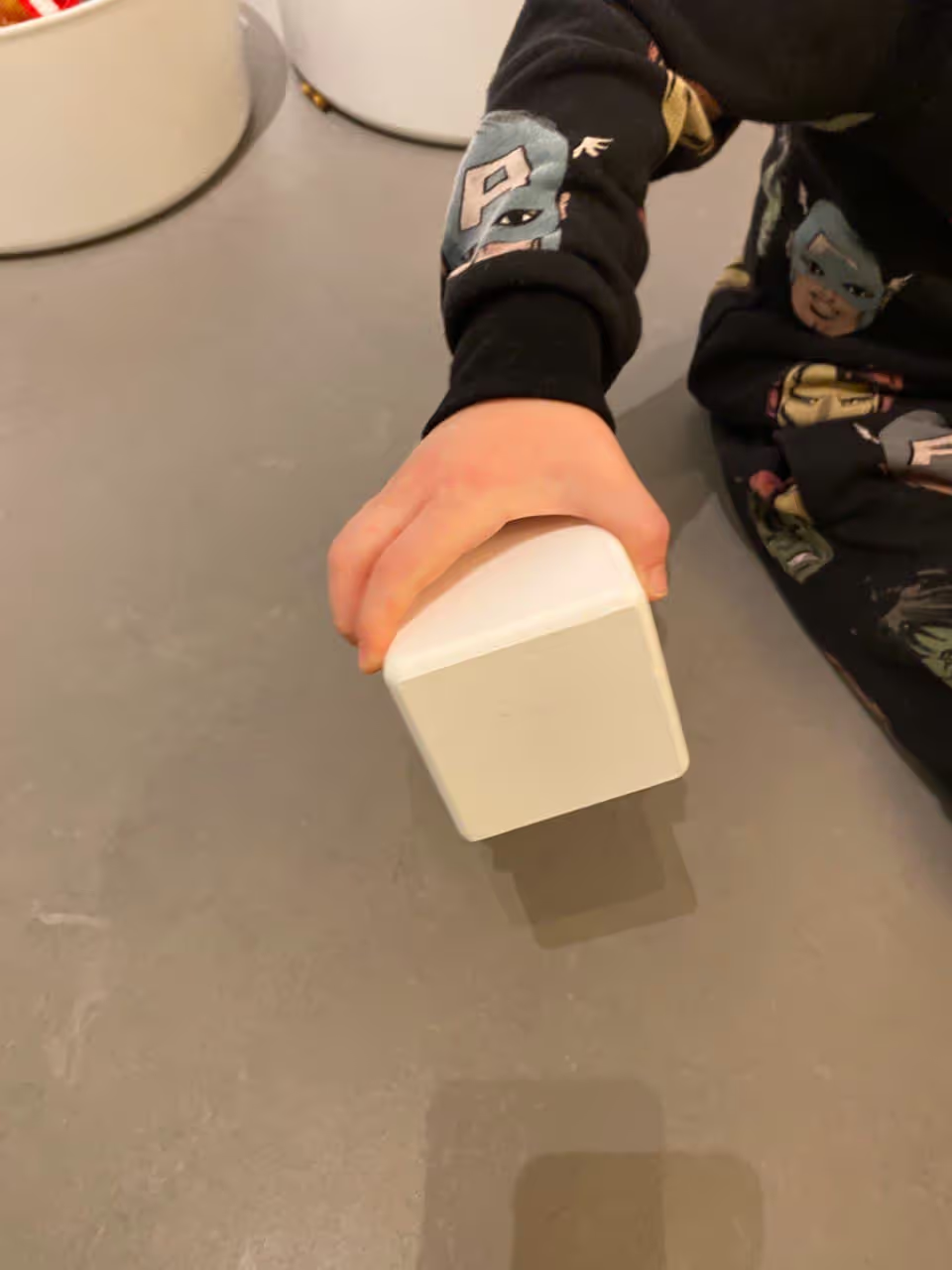

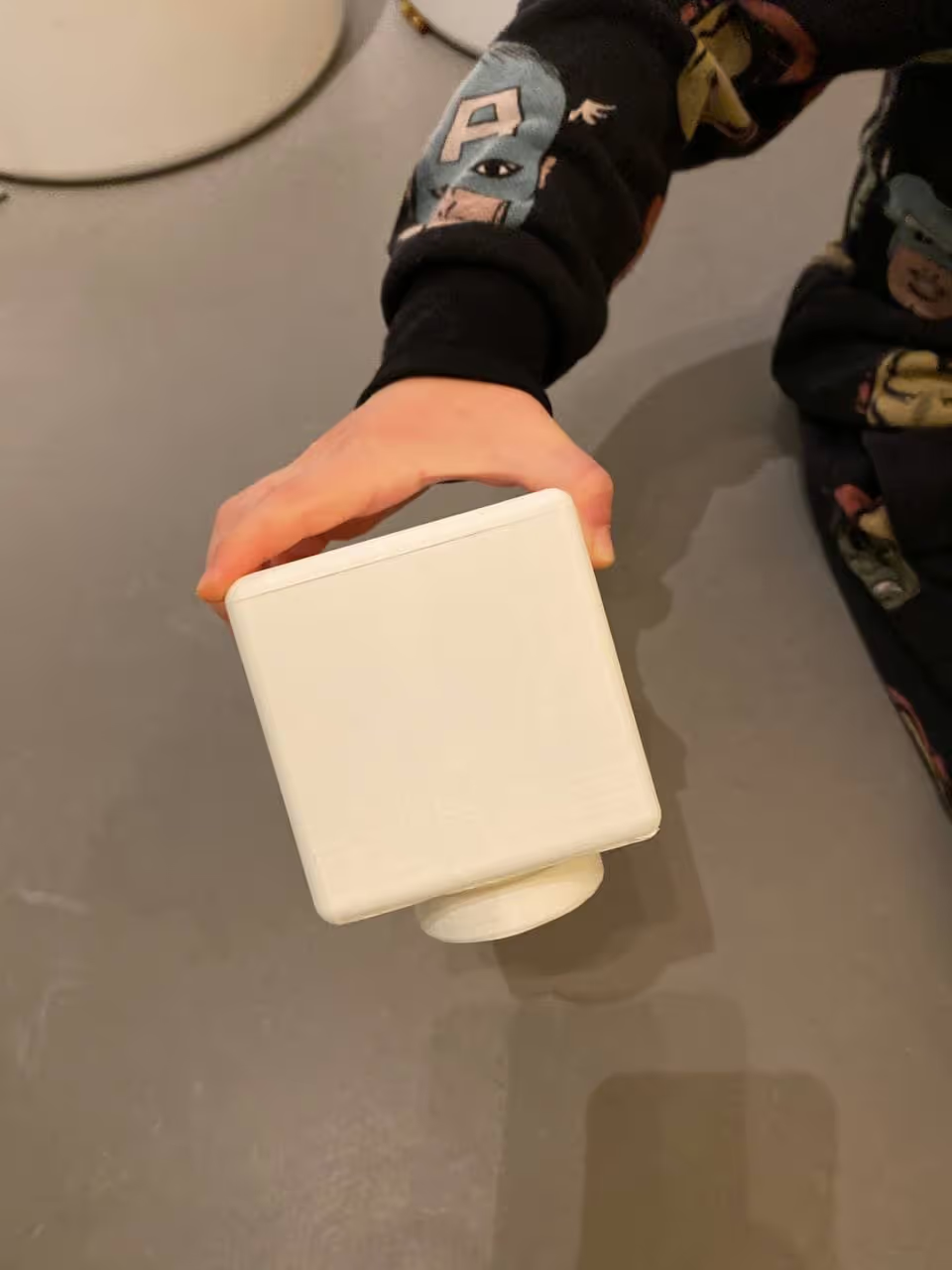

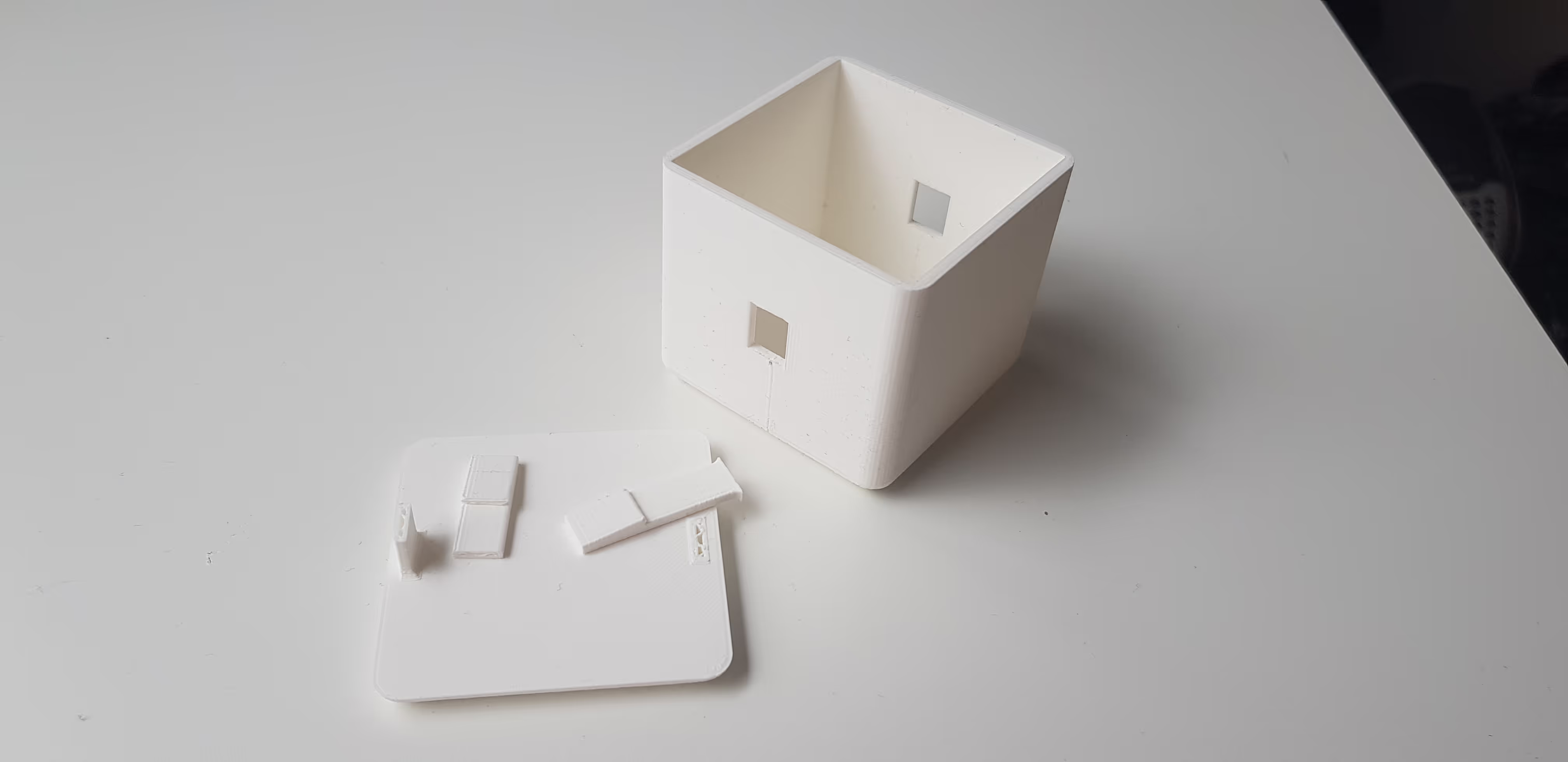

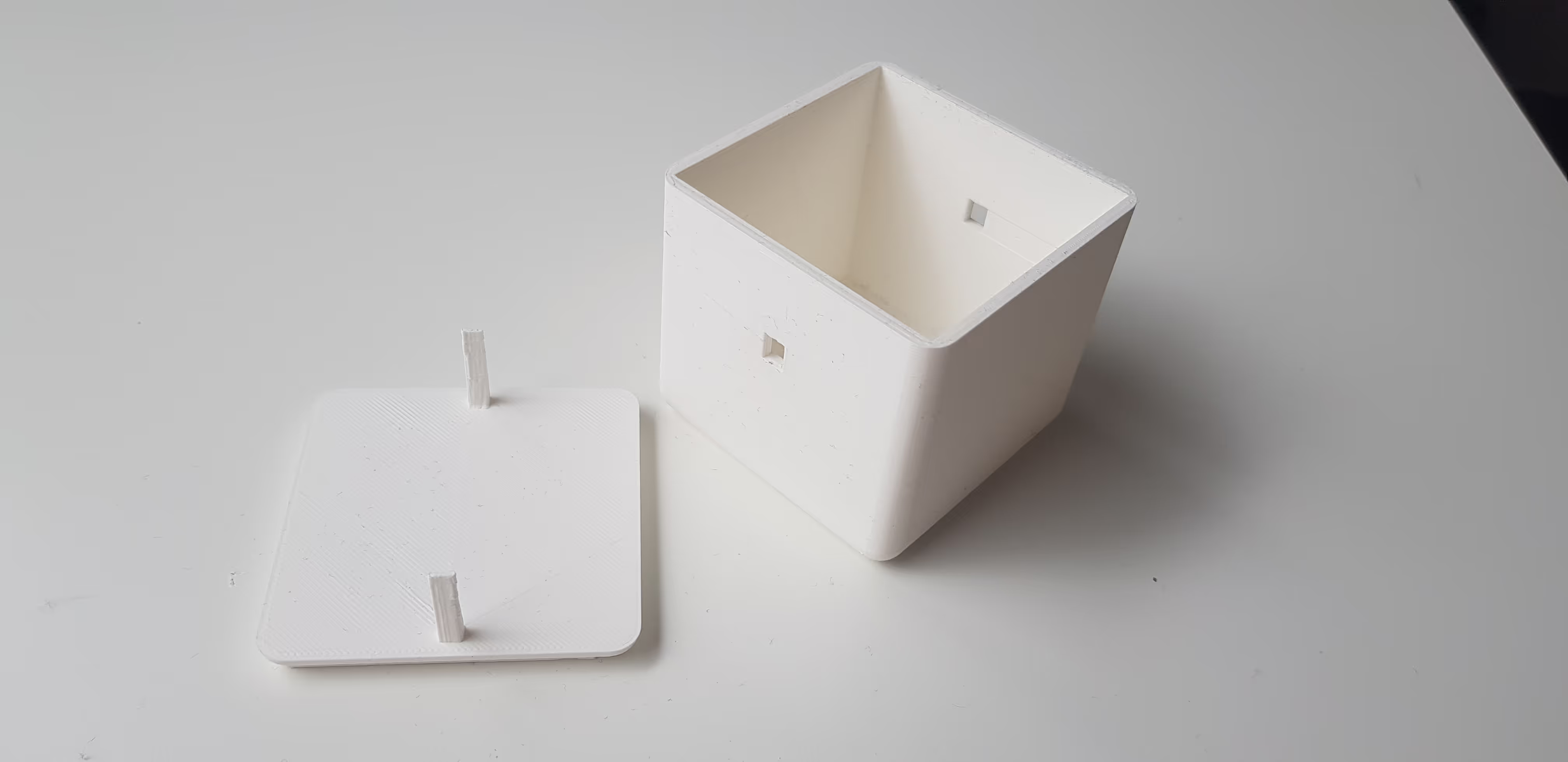

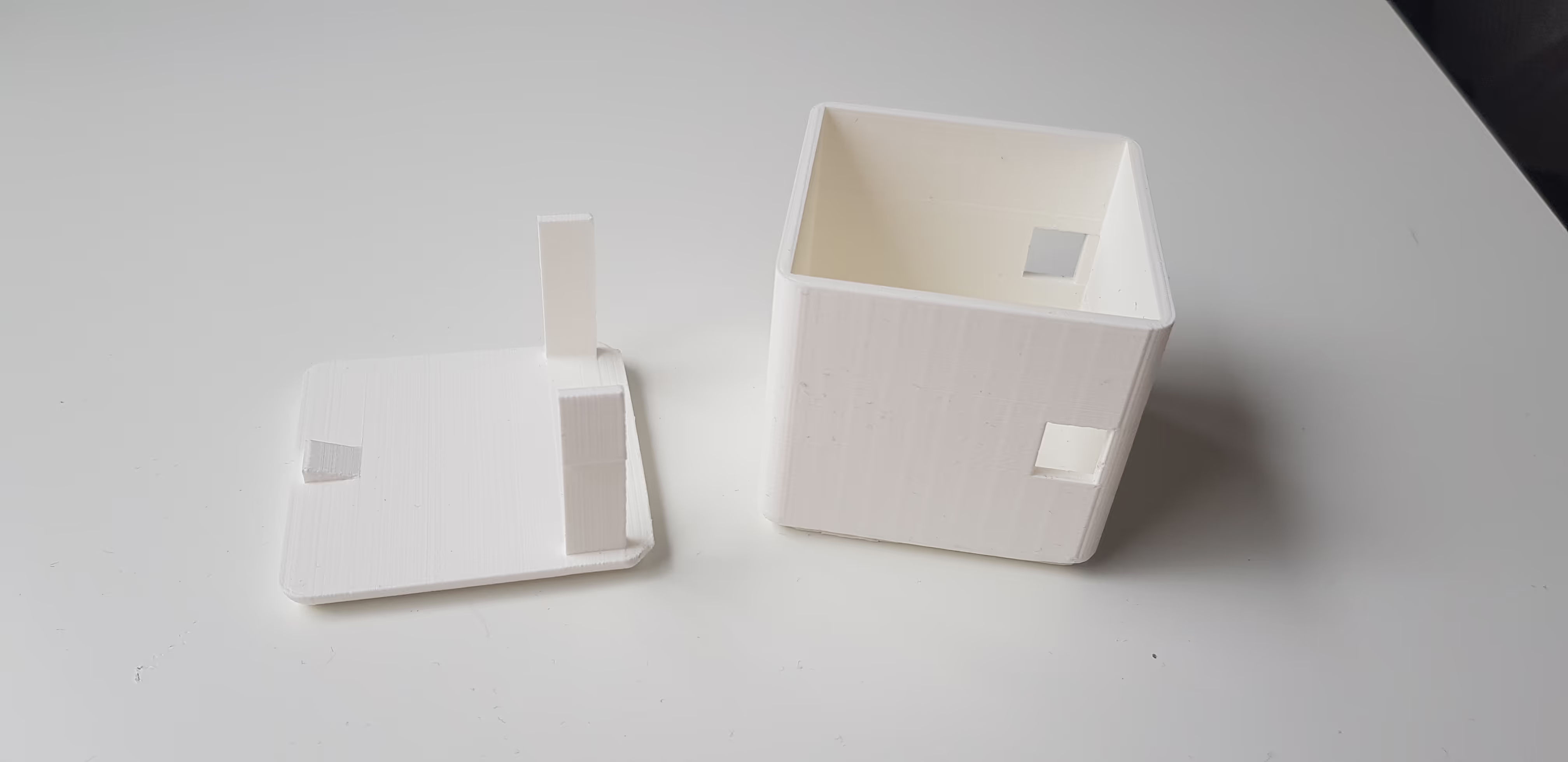

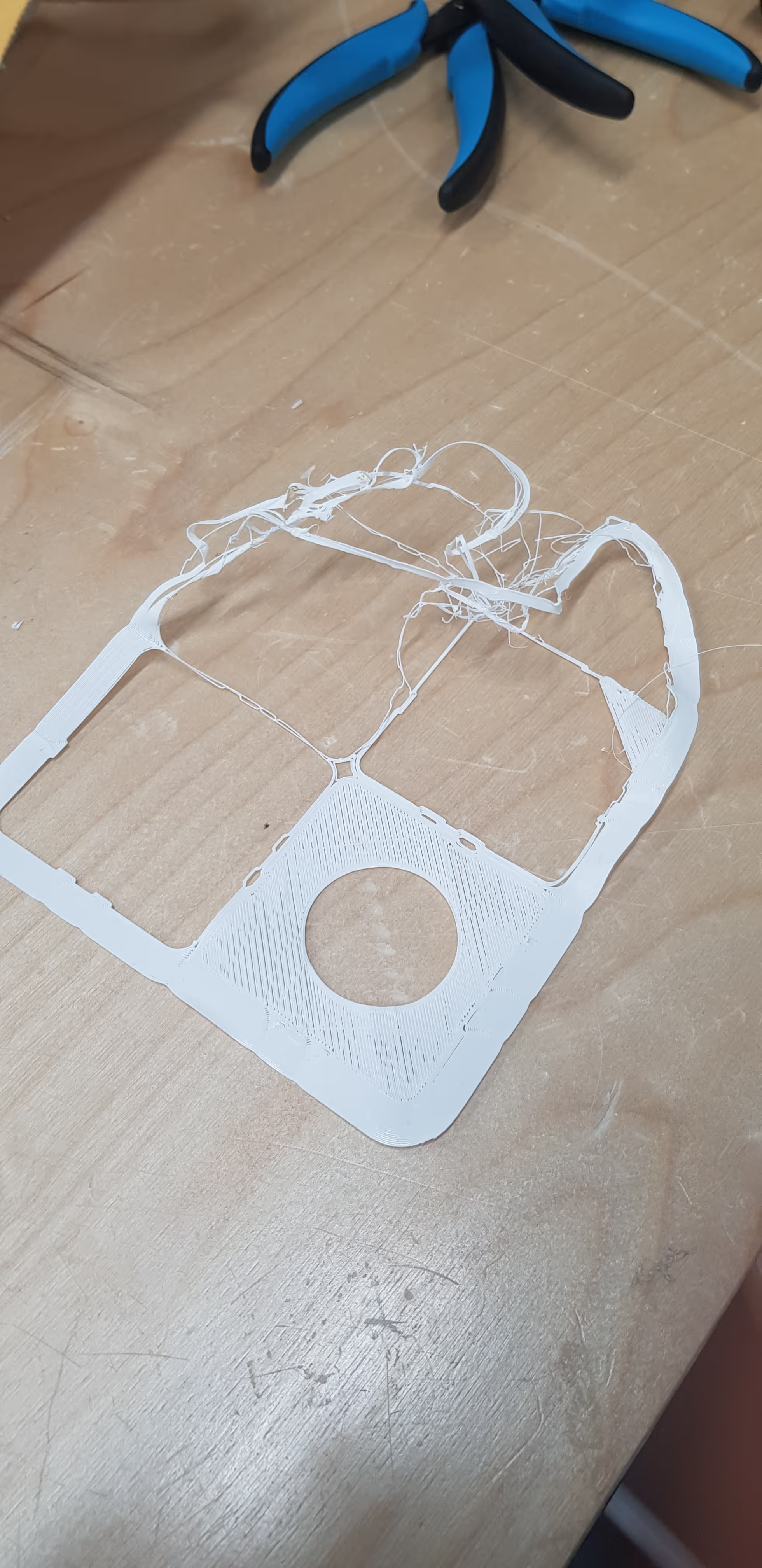

Producibility 🧱

Design with real-world playability, shareability and scale in mind.

Shared delight 🧸

Make the game engaging and enjoyable for sighted children as well